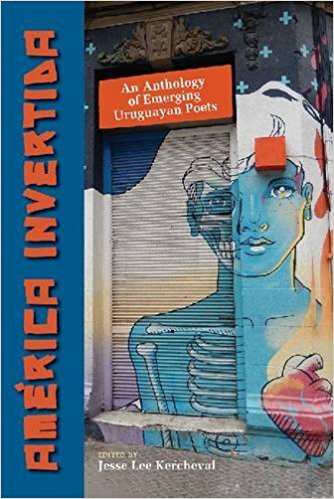

AMÉRICA INVERTIDA

AN ANTHOLOGY OF EMERGING URUGUAYAN POETS

edited by Jesse Lee Kercheval

University of New Mexico Press, 2016

304 pages

Review by Brian Satrom

To juxtapose or meld together contradictions isn’t anything new in writing. After all, that’s part of the work we expect of poets. It should surprise us even less in a collection called América invertida, a title inviting us to imagine all we associate with America, along with the flip-side of that—including dualities of North and South America.

But the nature of those contradictions and the way they’re expressed in this bi-lingual anthology of 22 emerging Uruguayan poets clearly come from unique landscapes and mindsets.

Poems by Karen Wild Díaz and translated by Ron Paul Salutsky feature a woman who’s both hiding from and longing for the sky, as in “A House without the Sky,” where we read:

Before writing do not wash your hands

You will lose the essence

She does not believe in essences

Does not wash her hands and she writesShe can live in a house without the sky but

cannot stand to be indoors for long

The longing lives always in her

and beyond

Repetition of phrases drives together a range of opposing ideas, including the way one behaves despite one’s beliefs, and tiring of the outdoors while still reaching for the sky and the unknowable. All seem part of a larger compulsion that has the feeling of a trapped, constrained life.

Fittingly, this piece concludes the collection. Many others throughout express similar conflicting themes of hope, despair, longing, and constraint, but with different tone and language. Javier Etchevarren, in his poem “Garbage Dump,” translated by Don Bogen, writes:

where there are people there’s garbage

where there are people there’s hope

including the hope to live off garbage

His poems, through blunt irony, evoke the contradictions of poverty and take us into worlds of a glue-sniffer or, as in “Lung,” what it is to “live off that death” when having to live and breathe in a toxic cloud.

Some of Augustín Lucas’s poems, which also portray the poor, fix on neighborhood locales as if a camera’s been left running while the protagonists of his poems, including transients, shadows, and inanimate objects, act out their moments. His prose poem about the Avenida General Flores, called “General Flores without Flowers,” ends:

General Flores walks in its sleep, and the furniture and the prices quiet down even more, and the beds cool down even more, the plazas and seductive shop windows lower the voltage of the lights, until it is sparkling, dry, free of shadow play.

Lucas’s poems are translated by Jesse Lee Kercheval, editor of the anthology. Kercheval’s vision brings together diverse poets under 40 in a country with a disproportionately high number of poets for a population of only 3.3 million. Her approach includes pairing each writer with a different translator, hoping to draw on a deep-rooted tradition of exchange, as she mentions in her introduction:

From Robert Bly’s seminal translations of Neruda and Vallejo on, these intercultural exchanges have been crucial to the development of poetry in the United States, opening up our vision of what poetry is, not just in America, but in the Americas.

The anthology is a true tapestry rather than dominated by a single vision or voice.

We’re given often five selections from each poet, whose works span a range of tone, abstraction in imagery, and subject, contrasting office workers and transients, urban and rural, present and historical past, and South and North within Uruguay. In "Night Up North" Fabián Severo writes of Artigas, a town in the North, by saying:

Artigas is an abandoned station

the hope left behind by a train that won’t come back

a road that disappears heading south.

Severo, with Dan Bellm as translator, claims this place that’s been culturally marginalized as the source of his identity by writing:

Before

I wanted to be from Uruguay.

Now

I want to be from here.

In an everyday expression of presence and absence Laura Chalar, translated by Erica Mena, describes an urban street scene with the all-embracing, tender vision of Whitman, but also the view of someone ready to leave. The prose poem “avenida 18 de julio” ends:

the man who just bought a smartphone, the woman who recites poems on the bus, the shoe shiner, the people handing out flyers for loan sharks or massage parlors, and me, who watches it all with the love of someone who is bound to leave, someone who is already leaving.

Images of desire, injury, constraint, and freedom conspire in lines of Paola Gallo and translated by Adam Giannelli, with the subject coming out of a dream in “I Smell of ‘Amber Parenthesis’”:

You were delayed by the awakening from a murky dream.

Aquatic Ophelia, conspicuous vibration

anointing in abundance your own bones.This poem is the wind arriving to air out the enclosures,

“wing of a cowardly bird,” you call yourself, I call you wound, litany.

Gallo’s writing doesn’t let us fully pin down meaning, which is both wonderful and unsettling.

Elisa Mastromatteo’s poems, translated by Orlando Ricardo Menes, come across as simply-spoken monolog but are effective in keeping us a little off-balance with the uncertainty about their external circumstance. In “Game,” we’re not clear what kind of game someone is acting out:

your manner

of murmuring by shuddering

of whistling by shaking

of flying by alternating

elbows and feet.

And almost always, or indeed always

your eyes being life itself

your soul so present.

Regardless the circumstance, which often feels just outside the frame of her poems, her tone can convey an amazement at finding oneself present.

As with any work of translation, for all the poems in this collection it’s hard not to consider what cultural context is just outside our view.

But even when set in unfamiliar contexts, the absences and presences, the urgencies for flight and arrival in the poems of América invertida often seem surprisingly familiar. Though ostensibly we’re presented with things foreign and far away, the poems can feel very much about ourselves.

Return to table of contents.