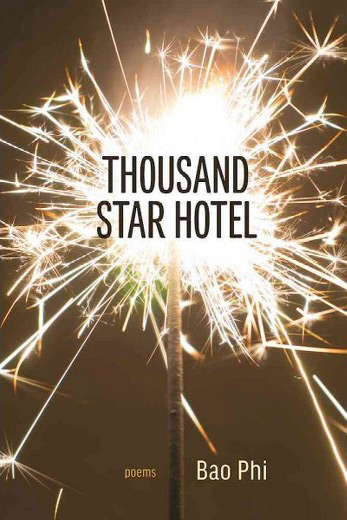

THOUSAND STAR HOTEL

by Bao Phi

Coffee House Press (2017)

110 pages

reviewed by Brian Satrom

What authors empathize with in their work can reveal a great deal about their perceptions of themselves. The poem “Not a Silverfish,” toward the end of Bao Phi’s second collection, Thousand Star Hotel, has the speaker imagining the perspective of a centipede trapped in his bathtub. After sharing that centipedes often get mistaken for silverfish when in fact they eat silverfish and other pests, Phi, a Minneapolis poet, writes:

I know what it’s like to be mistaken for something else,

to feel that the first reaction when a new set of eyes encounters your body

is to want to smash you. (p. 102)

Through Phi’s poems we get a glimpse of what that’s like and the effect being “invisible until revealed to be ugly” has on the range of human experience, especially love. We see how the nature of love—including love of family and self—becomes entwined with the way we’re perceived.

In “Go to Where the Love Is,” a poem about what his mother endured over the years, the poet writes:

More than two decades ago she was squatting,

fixing up damage

someone had inflicted on the easiest of targets:

the gooks in the hood.

Across the alley,

a multiculti rainbow of boys

shouted insults at her,

Asian and Woman,

forged in translation into slurs

cutting and rusted (p. 9)

That he feels helpless to do anything but stand there illustrates a powerlessness echoed in many of his poems. But when years later his mother sends him home with food she’s made, the poem ends with an affirmation of love in the lines, “Love is not neutral. / Never.” (p. 10) This conviction gives a sense that love both surpasses and is forged by what’s been endured.

Phi grew up in the Phillips neighborhood of Minneapolis, a son of Vietnamese immigrants. A multiple-time Minnesota Grand Slam poetry champion and National Poetry Slam finalist, Phi has honed a direct tone that encompasses a range of contradictory feelings. The effect is one of anger, humor, self-deprecation, and blunt self-examination in tension with each other.

The prose poem “Document” documents a range of racist incidents and the resulting feelings of inferiority the speaker would like to bury, but that eat at him anyway. It starts:

Let’s say the smart white girl from the wealthy family that you always thought was so pretty ends up being part of your study group, and she comes to your house with the others to work on the final project. She wrinkles her nose and asks if there are roaches, and instead of hating her you hate your mom and dad. (p. 65)

Phi portrays himself not only as victim but participant in the destructive currents of racism, one who when young accepted a vision of himself and family as people “infesting this place.” While the power and wealth dynamics of race are very visible in his work, the poet looks frankly at himself and those around him in exploring the spiritual costs of racism, including surfacing his own feelings of guilt.

Those feelings become even more complicated when he reflects on his relationship with his father. In “Lead,” when his father complains someone is shooting at his back with a BB gun, the speaker refuses to believe it, wishing his father were just normal:

I wish I were somewhere else.

I fancy myself Luke Skywalker of the hood,

in lieu of white skin and blue eyes,

a towel for a cape and a flashlight,

instruments that make me a good guy. (p. 11)

When he remembers helping his father remove the pellets from his skin and wash the wounds, Phi writes:

Darth Vader had a son who could not understand

his father had been corrupted into killing the best version

of himself.My dad had a son who thought he was just another gook

who didn’t know what caused him pain. (p. 12)

Imagining himself as a hero is a way of escape, but when the situation plays out in reality he feels the opposite of a hero, that he’s let his father down.

This is one of a number of poems showing the speaker translating feelings of powerlessness into hero fantasies. The mash up of popular American culture with immigrant experience in Phi’s writing can be humorous. For instance, in “Night of the Living” he writes:

In my dreams I am granted powers to slay,

put down the dead

the way some would plant rice—

alpha male without the attitude

or entitlement—

I just want to help, I’d say.

My family would be in some far, safe place (p. 90)

But the underlying themes of desire for some sense of control, to be seen as beautiful, and to be able to shield loved ones from hate are real. This is most poignantly conveyed when he writes about his daughter. In “Kids” we read:

How much energy will I spend trying to defend her against men not at all like me

and exactly like me

You can’t protect her [...]she wears the easiest part of you to see

she wears the worst part of you

she wears your face (p. 18)

Sometimes Phi’s work expresses exasperation, as in the poem “At Dinner,”—the speaker unable to fathom those who make slurs “without once even considering / what we have survived” (p. 48). To not consider the possibilities of others’ experiences and histories is to deny them their humanity.

In another poem he recognizes that making assumptions is something even he does, though that doesn’t excuse it. “Therapist 4” starts with a therapist telling the speaker his mind “is swollen with doom.” Then the speaker moves on to speculation about an Asian couple at Minnehaha Falls in Minneapolis who ask him to take a picture of them, where we read:

If it sounds like I’m making assumptions about them and me,

I am,

and it’s not okay

just because I’m Asian too. (p. 86)

The poem includes a wish, expressed in other poems as well, for the ability to break beyond these dynamics of race, of trauma and loneliness, as if that were possible. It ends:

Each raindrop doesn’t care

if it’s the one to soak in

or the one that stays above it all to flood.

They just throw themselves on top of each other

until they become bigger than who they were

when they were apart. (p. 87)

But escape from the burden of race, feelings of doom, and his individual experience is a luxury not available to him. Through his work there is a sense of transformation, though, and of claiming control by naming it all. And by sharing all that with us, he broadens our understanding of experience.

Return to table of contents.