HIJROTIC

TOWARDS A NEW EXPRESSION OF DESIRE

by Subuhi Jiwani

photography by Tejal Shah

I first ran into the word hijrotic while I was listening to Radio Mirchi and travelling on Mumbai’s Harbour Line. RJ Jeeturaj was hosting his regular morning show and, as I was to find out, interviewing the well-known hijra rights activist Laxmi Narayan Tripathi. Of the many things she said, this one word stuck with me. Hijrotic, she explained, connotes something that is essentially hijra.

A hijra (pronounced hijada in Hindi) is a male-to-female transgendered person, who may be a transvestite, a transsexual, an intersex person or a castrated man. Hijras are seen with a mixture of curiosity and fear in Indian society and usually live in marginalised communities consisting of other hijras. Social and familial ostracism has led many hijras to form ghettoised communities but some, like Tripathi, are accepted by their families and continue live with them. Hijra communities are characterised by multi-tiered hierarchies, with the naik at the top of the pyramid, and gurus (leaders) and chelas (subordinates) below.

Hijras inspire a mixture of reverence and fear because of their perceived mythic powers, which can usher in good fortune or bad luck. Traditionally, hijras have offered badhai or blessings and danced at marriage celebrations, childbirth ceremonies or the inauguration of new businesses. In recent times, however, fewer people invite hijras to bless weddings or childbirths, and this has made the less privileged among them turn to basti (begging) and pun (sex work).^1

I came across the word for the second time in a newspaper article. Laxmi, who was being quoted, had used it to describe the account books maintained by Lata Naik, the head of the gharana (family of hijras) to which Laxmi had first sought admission. At first glance, it seemed a rather innocuous coinage, a word that performed a descriptive function. On plumbing its depths, it reveals an intrinsically trangressive nature. It marries words that, in popular imagination, occupy opposite ends of the spectrum of desire. By coupling the words hijra and erotic, hijrotic brings together hijra subjectivity, rarely thought of as desirable or desiring, and eroticism. It is, then, more than an adjective: it is an utterance, an act, of self-affirmation.

I invoke it here with special reference to Mumbai-based video, performance and photo artist Tejal Shah’s Hijra Fantasy Series, a collection of performative photographs with hijras that was part of the multi-media exhibition What Are You? (2006).^2 Shah’s theoretically informed oeuvre has been concerned with gender, sexuality, the body and the interstitial spaces that exist within these categories but are suppressed by binaries like male/female, straight/queer and normal/abnormal. Her interest as an artist lies in these spaces, which she opens up for exploration in her work.

The Hijra Fantasy Series recreates through dramatisation the fantasies of three hijra subject-performers – Laxmi, Malini and Maheshwari – as articulated by them in interviews with the artist. From the outset, Shah espouses a queer radical politics and attempts to establish a commonality of cause with her subjects under the banner of queerness. Shah felt that the secret desires of hijras, and, more generally, members of LGBTQI communities in India (of which she is a part), rarely entered the public domain and remained tucked away in the chambers of the mind. She felt compelled to give these fantasies form through real-time performance and visual representation. Shah also asked her subjects how they would like to be photographed and incorporated their wishes into her own creative process, to some degree.^3 Initially, Shah had thought her subjects’ innermost desires would revolve around becoming doctors, lawyers or politicians. Instead, she was made aware of her own assumptions and stereotypes when her subjects articulated hyper-feminine fantasies – of being Cleopatra, a mother and a South Indian film star.

Shah’s intention in What Are You? was to explore “the pliable language of gender”, taking inspiration it would seem from Judith Butler. In Gender Trouble (1990), Butler had argued against substantialist understandings of gender that claimed it was “natural” and underlined gender’s constructedness in language and discourse.^4 It is unsurprising, then, that such formulations seem attractive to queer subjects looking to challenge heterosexism and oppressive gender laws, and give credibility to non-conformist performances of gender.

The barge she sat in, like a burnished throne / Burned on the water (2006)

In The barge she sat in like a burnished throne/burnt on the water, the full moon bathes a reclining Cleopatra and her attendant Cupid in light. The barge adrift on quiet waters, floats; time has passed since the oars last parted the waters. The air is thick with a perfume breathed by Cleopatra; you get a faint whiff of it and are, like Antony, Cupid (shown here) and the city beyond the wharfs, intoxicated. She stares at you unblinking, unsmiling. She invites you to be a voyeur from where you stand behind the bushes. Her left hand rests casually on one breast; there is a vanity in that gesture, and an awareness of being seen, of being desired. Her expression and body language – cupped breast, supple navel, spread legs – speak of her sexual switched-on-ness and yet, you can see coyness in her eyes, even vulnerability.

You realise it isn’t you who own her with your gaze like an 18th century collector of Renaissance nudes might have owned (or thought he owned) the women in his paintings.^5 Rather, it is she who owns your gaze, directs it at her. Your eyes move along a three-point, vertical axis marked by her eyes, his erect penis (or cod piece) and his face. They anchor each time in the lower third of the image, in her eyes, where the vertical axis meets at ninety degrees the horizontal axis that runs along her body. Cupid, enamoured by Cleopatra’s beauty, is more or less a prop in the scene, which is dominated by her presence. He stands frozen and stares at Cleopatra, distracted and aroused.

Cleopatra here is being performed by the above-mentioned Laxmi Narayan Tripathi. Through her performance, she lays claim to Cleopatra’s iconic desirability, which is, unarguably, a heteronormative construct. Laxmi’s desire is not particularly transgressive; it is where her desire is grounded, in her non-normative gender identity, that alters the way we perceive it. To state the obvious, Laxmi’s performance queers in a particularly Indian and hijrotic way the Cleopatra story. It becomes her public assertion of female beauty and desirability from a trans-, or, in this case, hijra location. The implications of this for our collective ways of thinking about female beauty are significant. The photograph challenges conventional ideas about the relationship between gender, beauty and desirability, and coaxes its viewers to examine their own ways of seeing. A beautiful woman need not be a biological female, it says in no hushed tones.

Dressed up in glamorous Bollywood kitsch, the image, coupled with its caption, creates a intertextual encounter: it brings together Shah and Shakespeare. The caption is a quote from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, taken from a famous speech by Domitus Enobarbus which describes Cleopatra’s inordinate beauty. Shah’s invocation of this epitome of the English literary canon (which, for Indians, is also a colonial inheritance) upsets conventional readings of the 16th century playwright-poet and queers his legacy. Shakespeare now frames a hijrotic assertion of beauty and desirability.

You too can touch the moon – Yashoda with Krishna (2006)

In You too can touch the moon – Yashoda with Krishna, a mother and child pose in a photographic studio for a portrait. A painted backdrop showing the moon completes the arc of vision along which your eyes travel, from the child to the mother to her outstretched hand to the moon. The setting is baroque, opulent, and the costumes fittingly so. There is tenderness in the mother’s demeanour: she envelopes her child in a loving embrace. She gestures to him that the moon, ephemeral and ungraspable as it is, can be reached. He is engrossed in the present, as children are wont to be.

This performative photograph features Malini, whose secret desire it is to be a mother. Shah’s decision to paraphrase in the caption what the mother tells her child, inflects it her own voice. Shah seems to be saying to Malini, in a slightly patronising tone, that she too can touch the moon, which becomes a metonym for motherhood. The caption reveals the artist’s desire to open up motherhood, make it relational and disassociate it from biological reproduction.

In the second half of the caption, Shah invokes a painting also called Yashoda and Krishna by the famous Indian painter Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906). In fact, the way the image has been composed, the position of the subjects within the frame, their lavish costumes and their gestures, bear a striking resemblance to the original. In her artist’s statement, Shah said that her reference to this opulent painting – and consequently, its recreation here – helped hijras "transcend the class hierarchies that prevent [them] from moving into any position of power or privilege, even if momentarily" (italics mine). While these strong words highlight the forced marginality of hijras, they also generalise using a victimising tone.

That said, by ‘casting’ Malini as Yashoda, the shepherdess who adopted the naughty child-god Krishna, Shah reminds the viewer of myths related to hijras, cross-dressing and sex change in the Vedas, Puranas, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. By doing so, Shah attempts to destabilise the ground on which Varma’s nationalist-utopian vision of Hinduism, its deities and the Hindu woman stood, implying that these figures could very well be androgynous or queer or hijrotic. The image may not be hijrotic in the way that the previous image is, that is, it may not highlight hijra desirability, but it foregrounds hijra parenthood which is still not a widely accepted phenomenon.

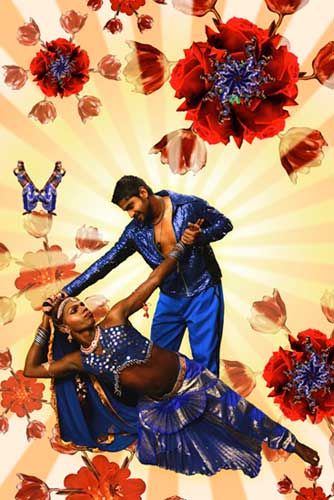

Southern Siren - Maheshwari (2006)

Finally, in Southern Siren – Maheshwari, we see Maheshwari and her lover entranced by each other’s gazes. They are frozen in a still from a South Indian film, caught in the middle of a song-and-dance sequence. They look deeply, adoringly, into each other’s eyes. While he is enraptured by her presence, she seems aware of our looking at the scene from beyond the frame.

Southern Siren – Maheshwari diverges from the other images by moving away from realism and creating a nowhere space of celebratory camp. A light source behind the ‘hero’, who is positioned in the centre, radiates outward and engulfs both lovers in its glow. The expressions on their faces speak volumes about their relationship and especially, the former’s self-affirmation. Maheshwari’s body may differ significantly from the voluptuous South Indian heroine’s, lanky and muscular as it is, but within the fantastical diegesis of the photograph, that is immaterial. Her lover’s smile is coy but desirous, while her stern, almost aggressive expression seems to say – to the hero and to us – ‘I’m hot and I know it!’ Her position in the photograph, spread as she is in the foreground and overshadowing her lover in adornment, clearly establishes her as the subject of desire. And the caption only reinforces this.

The red roses dispersed across the image, from which radiate more roses and miniature Maheshwaris, allude to the gulabi or queering nature of the scenario that Shah has set up. The rose is a popular icon of the queer movement in India and its genealogy can be traced back to classical Perso-Urdu lyrical poetry in which it was used as a metaphor for same-sex/queer love.^6 It is also reminiscent of the kiss in older Hindi films which was never shown explicitly but alluded to by the metaphorical coming together of flowers. The roses, by occupying the edges of the frame and not centre-stage where the romantic exchange occurs, reinforce that that this queer romantic scene needn’t be hidden from public view.

Maheshwari’s desire to be a South Indian cinema star echoes Laxmi’s: they both desire desirability but articulate that wish in different emotional tones – the former as assertive yearning, the latter as aggressive want. Maheshwari’s performance is hijrotic much like Laxmi’s and it successfully queers the popular South Indian film song.

These hyper-feminine performances of idealised selves seem to be taking place in what Livia Monnet has called “a fabulous parallel world of perverse otherness”, a world of queerness which Shah depicts as not-quite Other, in fact, as ‘normal’ within the world of the photograph. The intertextual encounters Shah sets up in which Shakespeare, Raja Ravi Varma and popular South Indian cinema meet hijrotic articulations, help to queer hegemonic sites and foreground desires rarely seen in the mainstream Indian media. While Shah invokes “the pliability of gender” as the progressive theoretical peg on which this work and the identities of her subjects rest, one cannot help but wonder if this Butlerian idea just might hold more weight for the artist than it does for her subjects. Looking at the images themselves, it would seem that a deep-seated desire for the mimesis of femininity – and not gender ambiguity or unfixing – drives the subject’s performances and fantasies. Even if their acts might contribute to the denaturalisation of gender.

References

1. Rushdie, Salman. 2008. “The Half-Woman God” in A. Sen, N. Akhavi, P. Panjiar (eds.) AIDS Sutra: Untold Stories from India. Canada: Anchor.

2. What Are You? opened at the Thomas Erben Gallery, New York, in May 2006 and showed again at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, Mumbai, in September 2006.

3. In an interview with this writer, the artist said that while the process of creating these images was collaborative, the images themselves are her own creations. Thus, while her subjects were consulted, most of the aesthetic decisions were primarily made by Shah.

4. Salih, Sara. 2002. Judith Butler. Oxon: Routledge.

5. Berger, John. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin, pp.45-64.

6. Monnet, Livia. 2006. “’Queerness in/as the Strange, Prismatic Worlds of Art’: Fantasy, Utopia, and Perversion.” Artist’s catalog, Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, Mumbai.

Return to table of contents here.