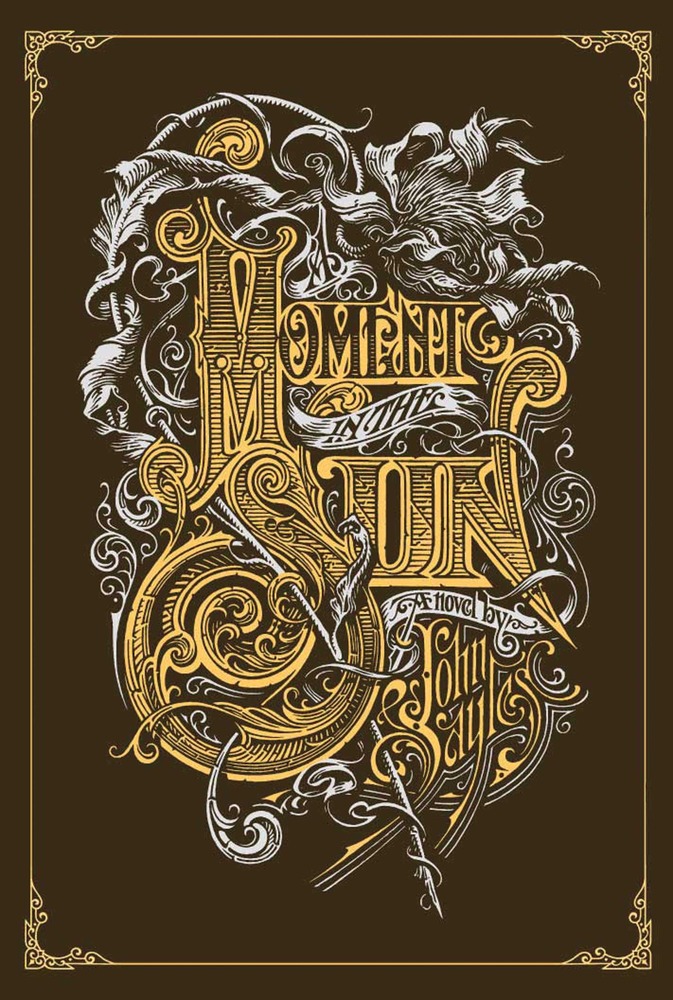

A MOMENT IN THE SUN

by John Sayles

McSweeney's

968 pages

reviewed by Terrance Getberlet

The Spanish-American war: vehicle for John Sayles’ newest film, Amigo, and his newest novel, A Moment in the Sun. Spreading awareness of the war has become his cause du jour and he’s been seeking answers as to why it figures so dimly in the American consciousness. It doesn’t have the cultural cache of most major American wars, falling somewhere below the colonial nostalgia of the Seven Years’ War and at level with the Davy Crockett-fueled heroics of the Mexican-American War, to use an arbitrary and slightly callous ranking of war popularity. Lasting memories of the war are few and even the most enduring one of Teddy Roosevelt and his rough riders is a relatively small historical footnote. How many of us can recount its events? And what of its most significant outcomes? Cuban independence? Filipino liberation? Another victory of democracy? Not quite. Try the coming of age for American imperialism. According to one character in the novel, the war was nothing more than “a show staged by white men.” It was a passing of the imperialist torch. Adios, Spain. Hello, America.

Writer and film director John Sayles’ new novel not only focuses on the war, but it basks in over three years of Gilded Age American history from 1897 to the assassination of President William McKinley and the successive inauguration of the USA’s premier imperialist, Theodore Roosevelt. A Moment in the Sun is a nine hundred plus page historical epic of the United States’ growth as an imperialist power, of its newborn need to reconcile the republican ideals of the past with the imperial aims of the times, and of the people in and out of the country who feel the growing pains of this development.

Both of the presidents mentioned above briefly appear in the novel as members of an expansive supporting cast (other famous figures making cameos include Mark Twain and gunslinger Bat Masterson), but the narrative focuses on the stories of a Kansas miner, a Filipino revolutionary, and three Wilmington, NC families of differing status as they, like the United States, seek to reconcile past realities with present aims. The stories of the well-developed, vibrant, and engaging characters are spliced together by the shared drama of the Spanish-American war and cleverly structured in a loosely applied, three-part Hegelian dialectic. The major theme or question of the novel is one of reconciliation (or of how to arrive at a synthesis) and John Sayles explores it from many angles, providing for a compelling and gratifying read, but the leading theme forces itself upon the reader in an unintended way. There is a struggle originating off page which Sayles faces in reconciling a desire to recreate an authentic past with a competing desire to craft a taut and unflagging narrative for the present. (Though the novel is an epic, digressions are few and not a one takes the form of a long list of place names or a lengthy genealogy characteristic of older epic traditions.) Through the filmmaker’s panoramic lens we find characters and settings (ranging from the Yukon to Cuba, from the Philippines to New York) authenticated to such a high degree that the verisimilitude, especially in language, borders on the wearisome. Yet in the context of an undertaking of this magnitude, which features an impressive handling of geographical, cultural, and historical diversity, such an impediment as mentioned above is forgivable and ultimately a matter of taste, but there is one defect that is not so forgivable—defect that Sayles, also a film editor, would have done better to leave on the cutting room floor—and it consists of the uneven treatment of the characters in the story.

Chapter one introduces us to the first of several characters one could consider to be primary; it features perhaps the most loveable underdog in a novel full of them, the hard-luck miner from Kansas, Hod Brackenridge, as he risks his life and savings with thousands of other hopefuls for gold in the Yukon. Successive chapters introduce Coop, an African-American from Wilmington, NC, who is a convicted thief and fugitive; fellow Wilmingtonians and newly-enlisted soldiers in the army’s African-American 25th infantry, Junior Lunceford and Royal Scott, best friends born into wealth and poverty, respectively; revolutionary Diosdado Concepcion, a native Filipino, Jesuit-educated son of a Spanish-supporting landowner; and Niles Manigualt, a white Wilmington native, the scheming, gambling, prodigal son of a judge. Most of the primary characters are born into disadvantageous circumstances, and they attempt to reconcile their pasts with the present and future while they maneuver within and around the increasingly pervasive and elephantine phenomena of industrialism, capitalism, and racism. Even the United States grapples with an ‘ism’ (imperialism) and each of the three parts which divide A Moment in the Sun represent a stage of development in the transition of the “land of the free” into an imperialist nation.

Part I, titled “Manifest Destiny”, introduces the reader to the childhood of American imperialism (its infancy is touched upon via the recollections of Hod’s Native-American friend, Big Ten) at a global level through the preparations of the United States and Filipino revolutionaries for war against Spain, and at a national level through the preparations of white Wilmington’s war on the rights of the city’s African-American citizens. At this point in the narrative, and in history, the United States still retains its reputation as a sincere proponent of republican ideals (a nation’s right to self-determination among them).

Part II features America’s adolescence as an imperialist nation. This second part is, in name and narrative, “A Moment in the Sun” for the Americans and Filipinos who both go to war and find success against the Spanish in Cuba and the Philippines. Also enjoying a moment in the sun are the white Wilmingtonians who find success in their war, culminating in the twin chapters, “Election Day” and “Posse Comitatus”. (The masterfully written chapters, whose titles refer to the legal means dubiously employed by southern whites to disenfranchise southern blacks, are two of the most suspenseful and poignant of the one hundred three chapters in the novel.) But for all parties—Americans, Filipinos, black and white Wilmingtonians—these moments in the sun occasion the beginning of a new era of degradation for both oppressed and oppressor, an era of uneasy imperialism, the antithesis of America’s treasured republican ideals.

The third and final part of the novel takes the name “The Elephant”; the title refers to one that is executed in a mortifying demonstration of Thomas Edison’s epochal harnessing of electricity, an act representative of the often dichotomous ends of Gilded Age progress (and of progress in general). “The Elephant” is a synthesis of contradictory ideals. The prevailing sentiment at the time is that the United States invades in order to liberate, engaging in imperialism to bring democracy and its associated republicanism (this sentiment is related to the reader through the point of view of a Hearst newspaper cartoonist), but Sayles also shows us the counterview. In this part we see the beginnings of American imperialism’s adulthood, as it extends to the Philippines in what is only a costume of liberation, shedding it soon after arrival to reveal a uniform of domination.

Sayles seems to ask his readers, rhetorically, if and how the United States can reconcile (or synthesize) its stated principles and its promises to the weak with its national and international practice of imperialism and exploitation. The answer to that question, of course, continues to bedevil us a century later. For most of the characters in the novel, however, Sayles provides captivating variants on the question of and the quest for reconciliation with resolutions that are not as elusive or unsatisfying as it is for the United States.

The theme of reconciliation is most transparent in and integral to the story of the Filipino, Diosdado Concepcion. He was educated in Jesuit schools, dressed in fine clothing, housed in relatively opulent habitation, and given many accompanying privileges of wealth made possible by the sweat of his impoverished countrymen. Though born into a much more advantageous situation than his fellow Filipinos, his sympathy and political ideology lie with them nonetheless, leading him to join the Filipino revolution. He is frequently reminded, though, of his thoroughly Spanish upbringing (his father is known as Don Nicasio) by particularly intelligent and headstrong soldier who is later put under Diosdado’s command, leaving him understandably conflicted on the question of his place in the revolution, his command’s legitimacy, and his own identity.

Identity plays a major role in the stories of Hod, the hapless Kansan, and Coop, the fugitive Wilmingtonian who later joins the army’s 25th infantry; both are forced to live under assumed names in order to hide from various authorities. While Coop simply wants to retain his freedom, avoiding capture and reincarceration, Hod’s crimes are of a less deliberate and definite sort, allowing him the liberty to develop a more complex desire of changing a life (and past) of misfortune into one where he can “somehow, though the exact strategy [is] unclear, make enough jack… to stop chasing the next piece of bread and…find a girl”.

Royal Scott also wants a girl, the sister of his best friend, Junior Lunceford. Royal is poor, however, and the Lunceford’s are rich. Dr. Lunceford, family patriarch, won’t deign to entertain the thought of Royal courting his daughter, Jessie, even though she herself wishes to be with Royal. The tired ‘love against all odds’ story is only a façade, though; Royal’s desire to find a girl is a symptom of a deeper desire to find a home. Royal’s skin color makes his hometown of Wilmington inhospitable, and the strange bases and places he passes through in the army pose obvious obstacles as potential homes. Magnifying Royal’s alienation is the contrast presented by Junior. He feels right at home in the army, even though the rest of the soldiers in the 25th infantry resent Junior’s prosperous, Caucasian-like background (an obvious parallel to Diosdado’s situation). Junior seeks to reconcile his skin color with his aim of earning rank and accolades in the army so as to open the doors of the overwhelmingly white institution to future African-American advancement. Sayles laudably intertwines the quests of reconciliation for Royal and Junior. At one point, Royal summarizes the relation between their goals by observing that, “Junior was here [in the army] to impress the white folks. I am here… to impress Junior’s sister.”

Niles Manigault is the narrative’s primary representative of white Wilmington. He is not, however, representative of white Wilmington, owing to his partial abandonment of his genteel upbringing (he is a descendant of former plantation owners) in favor of houses of ill repute and the company of indelicate characters of all stripes, including African-Americans. In his case, there is not only a need to reconcile past with present, but also present with future. His conflict between past and present is embodied in the persons of two father figures. On the one hand there is Niles’ mentor, saloon owner and boxing promoter Jeff Smith, a paragon of intemperance, extralegal business venturing, and raucous living; on the other hand is Niles’ father Judge Manigualt, the model of temperance, law, and propriety. Not surprisingly, Niles is one of the most wild, imbalanced, and complicated characters in the entire narrative. Many of his imbalances, shared by white Wilmington and most of the post-reconstruction south, seemingly stem from a single, common source: the emancipation. In this way, Niles is representative of his hometown and the region, since all appear to be haunted by the ghost of their antebellum glory days; they all face difficulty in adjusting to what they see as a downgrade in status. Niles, though, thinks it impossible to recover past glories without grossly exploiting or cheating others (unlike his father who appears to have maintained his privileged status by comparatively honest means). He is tasked with reconciling his present situation, of living below what he believes to be his station, with his future aim of making a return to the life of ease and luxury, a return to the plantation (which he tries to buy with severe consequences at one point in his story). Some of the most fascinating and transfixing chapters are told from his point of view, a view colored with racism and a sense of superiority—from a man who lives with and depends on supposed inferiors.

Not all of the aforementioned characters in A Moment in the Sun are as deeply and satisfyingly explored as Niles Manigault. Coop, for example, is one character who suffers from uneven treatment on the part of Sayles. The terminus of Coop’s story is ill conceived; there is an attempt to bring his development to a natural and fitting end, but it comes off as abrupt, and even a little cheap. The abruptness of that climax and his lack of emotional depth suggest that he does not rank as a primary character. Throughout the novel, though, Coop is written as if he is just that, having both a complete story arc and a great many pages and chapters devoted to furthering the narrative from his point of view. Here, Sayles struggles to reconcile the position of a character that, being a rather plain and uninteresting stereotype of a fugitive, would strengthen the narrative with fewer appearances and a reduced yet unambiguous and less problematic role as a secondary character.

There are also characters who, unmistakably in a supporting role, receive main character-like consideration with much distraction to the reader. Take Lan Mei, a Chinese woman forced into prostitution and into the novel as the love interest of one of the characters in the Philippines. She makes her first appearance a little less than two-thirds of the way through the novel, and her back-story almost completely subjugates the narrative for forty-five pages; her introductory chapter, ironically titled “The Wages of Sin”, is salvaged only by brief cuts to the main characters. Those cuts evince some realization on Sayles’ part that Lan Mei’s back-story is cumbrous, if not an outright burglary of the narrative. He desires authenticity, though. He wants readers to know the Philippines as a place shared by many Chinese who arrived under less than ideal circumstances, and his quick cuts are attempts to reconcile authenticity with the knowledge that this otherwise interesting, pitiable woman is a burden to the established pace of the narrative. Concerning Lan Mei’s long moment in the sun, the reader feels a germ of what the Filipinos must have felt when, after three-hundred years of dealing with Spanish overlords, some alien culture invades, forcing them to become rapidly acquainted with the ways and demands of an entirely new element that seeks to exact their recognition.

At a very late point in the story, eight-hundred pages deep into the lyrically generous and literally dangerous jungles of this novel, the reader is introduced, and subjected, to the story of an imprisoned man called Shoe, whose ostensible position in the narrative is to serve as a medium through which the details of a major, contemporaneous event in American history are related. Undue attention is given to the new intruder, however entertaining and authentically written he may be, as the narrative switches to his point of view for twenty-some pages that delve into his former life as con man and his more immediate experiences as convict. Perhaps understandably, Sayles couldn’t bring himself to execute this “little darling” of which William Faulkner spoke, yet it remains that much of what is told from Shoe’s point of view is tangential and interruptive of the narrative.

Furthermore, there is a preponderance of Gilded Age confidence-man lingo in the speech of the character, and though the meanings of it are determinable through context, it might frustrate some readers who aren’t as well acquainted with, or don’t find necessary, the lexicon of slang in which Sayles so clearly revels. Other chapters in the story carry similar baggage that could either please or confound, such as the chapters told from the point of view of an acerbically witty and engaging newsy, named the Yellow Kid (after his sickly complexion). Some readers might think his speech pocked with more of the same distracting, era-specific slang, blemishing an otherwise flawless chapter named “The Yellow Kid” after its featured character. The noteworthy chapter speaks of the United States’ impending war with Spain in Cuba, rendered poetically with the refrain, in bold, capital letters throughout, of “WAR!” (the way it might appear on the pages of the papers which the Yellow Kid is tasked to sell), but there are also paragraphs packed with slang such as this: “Boy Willie himself pulling up in his hack with… his glad rags. As far as they can tell he runs the dogwatch shift at his Journal… He always calls hello but never throws any mazuma their way.” And what is arguably effective above is undoubtedly discordant in other places. Look to the opening chapter of part II. It features two Irish immigrants speaking of current events in speech that is over-the-top in its authenticity and replete with period-specific dialect and marring misspellings, e.g., “Think iv all thim barefoot Fillypeeny byes who could be out rushin the cans fer the workingmen or shinin the shoes of thim what has shoes—“.

Of course, as the word ‘author’ indicates, it is most often vital for writers to render their stories in an authoritative and authentic manner, and most readers and writers alike would probably argue that it is better to err on the side of over-authenticity, of which Sayles is guilty and yet deserving of commendation. (His previous work evinces a strength in authentication: his 1995 film, Men with Guns, set in Mexico during the height of the Zapatista movement, was not only filmed in Spanish, in Mexico, using an almost entirely Mexican cast, but also written in Spanish by the bilingual Sayles.) The disturbances in narrative flow attributed to the unwarranted focus on some characters—and it would be a mistake to consider their moments as necessary releases of tension—are less forgivable, yet even they are relatively minor transgressions considering the volume of this work, Sayles’ most ambitious endeavor in print.

In light of the epic length and breadth, the clever structure, the memorable characters, the strong unity of theme, the gravity of the pointed attack on imperialism, it seems the strengths of the novel cast a long, large shadow over the weaknesses, whose moments of exposure to the sun are indeed brief. John Sayles fans will be intoxicated by A Moment in the Sun, imbibing an extra large dose of the familiar John Sayles style tonic, but it is a worthy read for others, especially for those taken by the idiosyncrasies and hypocrisies of the Gilded Age, and for those admirers of the narrative scope found in the novels of Thomas Pynchon and James Michener. In the end, with the ambition of this novel realized, John Sayles can rightly claim a moment in the sun for himself.

Return to table of contents.