A TOUR OF ANCIENT LYKIA

(A LETTER SENT TO ALBERT GOLDBARTH)

by Vincent Czyz

13 September 2006

Dear Albert,

A return to the art … or is it merely a craft? Of letter-writing. Certainly different from writing an e-mail, which is generally dashed off in a few minutes—a single sitting at most. But still different from the old days of pen and ink or even of the manual typewriter since back then corrections had to be made immediately or in the form of addenda.1

Point of interest: A mere ten years ago, when I first moved here, you could walk past a certain building in the Bahariye quarter of Istanbul and see five or six men sitting at manual typewriters. For a fee they’d type up a letter or, more often, an official form to feed some bureaucratic furnace. In Neuromancer William Gibson gives these Turks word processors, but they are, in fact, all gone—put out of business by Internet cafes and on-line forms.

From the radio I hear: “Do you know who I am? I’m Moe … Green. I made my bones when you were going out with cheerleaders.” This is a sound-bite I hear about a dozen times a day (this station plays mostly rock of the occident, throwing in tunes from as far back as the sixties). You probably recognize Moe Green from The Godfather, but I can’t help wondering how many Turks out there get these clips (another one getting air time is from The Blues Brothers).

This is gonna be a missive mostly about a trip Neslihan (my girlfriend) and I made to southern Turkey, what was once ancient Lycia (mistransliterated from the Greek, just like cyclops and encyclopedia and psyche and all those words that should have a kappa instead of c and which Guy Davenport corrected in his translations and stories)—so, Lykia.2

WHAT’S A LYKIAN ANYWAY?

We landed in Fethiye, which was Telmessos when it belonged to the Lykians. In the 8th century, it was called Anastasiopolis after a Byzantine emperor and then, for obscure reasons, it became Makri. The current name was taken from a local Turkish pilot named Fethi Bey who distinguished himself during WWI.

Now the Lykians … they were not, according to the latest scholarship I could lay hands on, another group of Greeks; they were indigenous to Asia Minor though some of their cities were renamed in Greek and their alphabet uses some Greek letters (more of that anon). They also fought under King Sarpedon on the side of Troy during the Trojan War. Hittite cuneiform texts refer to the nation as Lukka and the language as Luvian. The Lykians themselves apparently called themselves Trimilae and are now considered the oldest Anatolian tribe in the Mediterranean region. Their federation of cities generally resisted the rule of mainland Greece. They were so fiercely independent that Herodotus records this of the Lykians at Xanthos:

The Persian army entered the plain of Xanthos under the command of Harpagos and did battle with the Xanthians. The Xanthians fought with small numbers against the superior Persian forces with legendary bravery. They resisted the endless Persian forces with great courage but finally succumbed and were forced to retreat within the walls of their city. They gathered their womenfolk, children, slaves, and treasure into the fortress. This was then set on fire from below and around the walls, until all was destroyed by the conflagration. The warriors of Xanthos made their final attack on the Persians, their voices raised in their battle cries, until every last man from Xanthos was killed.

And then there is this bit of poetry, which comes, I think, from a Lykian inscription somewhere or other … I don’t know because my oh-so scholarly book doesn’t footnote it or otherwise cite the source!

We had turned our homes into graves and

graves our homes.

Our homes, destroyed, our graves plundered …

[…]

We, who preferred mass suicide for the

sake of our mothers, our women and our dead

we left behind a pyre of people to this earth, a

pyre that doesn’t burn out and will never cease

to burn.

It’s a moving fragment wherever it came from—the event a combination of Thermopylae and Masada more or less. About once every two weeks or so, I daydream about a piece of fiction that tells the story. (More on Xanthos anon.)

In 296 BC one of the Ptolomies banned the Lykian language, replaced it with Greek, and forced all the Lykian cities to adopt Greek constitutions (the Lykians didn’t fight Alexander when he showed up cuz they were still pissed at the Persians but after the death of Alexander, got handed around among various despots—such as the Ptolemies).

ÖLÜ DENIZ

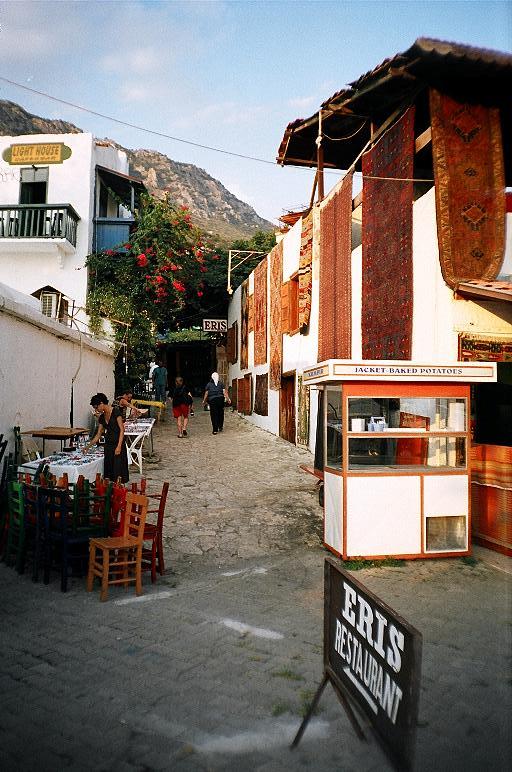

Fethiye is a modern Turkish city, a small one, right there on a bay of the Mediterranean. Economy’s based on tourism and fishing although most of Fethiye isn’t all that scenic. The city is somewhat dirty and run-down, but there are a few good-looking areas as well. One of them is a small maze of narrow cobblestone streets blocked off to cars; this is where most of the bars, restaurants, clubs, and tourists congregate. There are some beautiful houses with interesting variations on Turkish architecture. There is also the sea-scented air—where it’s not choked with jasmine—they love to bury trellises here in jasmine, and the smell is actually hard to breathe it is so thick in places. Lemon, orange, and olive trees abound, as do grape vines (with still-life perfect clusters hanging from them).

Our first full day in Fethiye, we went to Ölü Deniz (this o has an umlaut over it and is pronounced like the o in worth … ölü designates dead and deniz means sea) … but it’s far from dead! The name came about because the sea is so calm here. It’s an ideal setting for a beach, which is long and curving with some cliffs—a few shades darker than the orange of baked clay tiles—towering over its eastern end. Lots of paragliders soaring over the cliffs and landing near the beach. About $60 if you wanna go up with a pilot at your back.

I was enjoying swim until I inhaled just as a wave hit me head-on. I swallowed enough water to make me vomit—almost. Some in my lungs and nose as well, so I was coughing and retching and treading water at the same time. The lesson here, I reckon, is double at least … 1. don’t get too comfy in the sea, and 2. the future’s uncertain and the end is always near (‘Roadhouse Blues,’ of course). Reminds me of a line from Virgil’s Aenid,which will attempt to recall: “O Palinuros, too trustful of the deceptive waves, on an unknown shore naked and dead you shall lie.” I used it as an epigraph for a Master’s essay about twenty years ago.

THE STONE VILLAGE

After a few hours at Ölü Deniz, we made for Kayaköyü, “the largest late-Medieval ghost town in Asia Minor” according to my guidebook. What happened you ask? Well, the Greeks fought their war of independence against the Turks in 1821—and won. Then in 1919 the Turks fought their war of independence against the Greeks—and won. That is, France and England saw a chance to carve up Turkey and backed an army of 200-250,000 Greeks to go ahead and take back Asia Minor. This war caused so much material damage to Turkey, you almost forget the loss of human life. Ancient Smyrna, modern-day Izmir, was burned to the ground and, while the Turks are almost certainly responsible for starting that fire, numerous other towns and villages were torched by the retreating Greeks. Me, I don’t blame anybody: the Greeks had suffered under the Turkish yoke for more than 400 years, but then they’d ruled the world under Alexander, who was no Mr. Nice Guy. As for the Turks, they were trying to salvage what they could of their independence and the Ottoman Empire—which is now the Turkish Republic.

Well, some years after this war, Europe supervised a population exchange between Greece and Turkey … thousands of ethnic Turks were deported from the Greek islands and the mainland and sent to Turkey; thousands of ethnic Greeks were similarly sent packing. This was the case with Kayaköyü, which means stone [kaya] village [koy]. A Turkish name that bears no relation to the place or its inhabitants, who called it Karmylassos. After the Greeks vacated 2,000 or so homes, the houses were bestowed on a group of Muslim Makedonians who refused to live there, believing the Greeks cursed their homes before they left (I bet they did!).

There are two churches in Kayaköyü. Beside one of them, was a charnel house (which I could not find) filled with human leg bones. The departing Greeks dug up the remains of their ancestors and took the skulls with them to Greece. Why they piled up the leg bones beside the church no one seems to know. (Here is another story I’d love to write although I am neither Greek nor Turk. Of course, should I attempt it, yet another acquaintance or friend will say, why don’t you write what you know? Why don’t you write about your brother the boxer? Etc.)

As we headed up a slope to Kayaköyü, I said to Nesli, “Where’s the camera?”

While I was standing there being miserable and berating myself for losing half the reason for taking any trip, I noticed a dog with about 7 inches of furry black goat leg—including the hoof—in its mouth. Wearing a collar, it growled at me when I approached, and off it went with its prize, one end of which was red and raw.

Camera-less, we made our way to the abandoned village, which spread up and down the slopes of several wooded hills.

The village might be a poem in stone, depending on how you define poetry—lyrical anyway. I don’t now how, in a mere 83 or so years, the houses degenerated so badly—the wooden roofs are completely gone (no evidence of timber at all), no window is glazed, walls have collapsed, hardly a single house is whole. Only the churches have more or less kept up their structural integrity (built ’em like forts back then cuz sometimes … they were).

All you hear, standing on one of those slopes, are chirring insects and bleating goats.

Neslihan and I separated for a while and when she came back she surprised me by saying, “I saw a ghost.”

I said, “What?” They don’t use the term “ghost town” in Turkish and I thought Could she have?

Then she answered me in Turkish: “Bir kechi.”

I laughed. “A goat,” I corrected. “You saw a goat.”

Neslihan, by the way, is studying to be an environmental engineer. She is a mere 24 years old (as of the 24th of this month) and the 21-year difference, I know, is going to come back to bite us on the ass. But we get along extremely well, and we have the same sense of what is memorable, ugly, unjust, valuable. In other words, not only do we want to take pictures of the same things (when we have a camera), but we also want to frame the shots the same way. I can’t imagine being this comfortable around anyone else.

Anyway … it’s pretty much impossible for me to describe the late afternoon light on the eroding stone walls, as seen, for example, through the doorway of the Upper Church (no door of course).

From my journal:

Looking south from a terrace next to the church, there is a slope about half a mile distant, and the light is so thick it’s a gold mist coming down on a hard slant. The edges of the houses are almost blurred, but the effect, maybe, is more like haloing—except there is nothing round. Not a crown of light, more like an aura … borealis is north, this is the aura (not aurora) a la Mediterren. You can’t see the water, but you know the sea is there just beyond the hills.

Every house has a chimney and every chimney looks like a tiny tower with 8 windows (about big enough to frame a squirrel’s head) and a peaked cap like a roof on a cottage. Where plaster still smooths walls made of stone blocks, there are often the remnants of paint—red and blue are the only two colors we came across.

I watch the shadows of tall grass gone to seed sway on a wall. And we both wait as though we can see evening falling.

THE PENSION

Back in the pension I felt very clean. It wasn’t just that my sinuses had been cleared out by the swim, not just that I’d been scrubbed down with salt, but I felt purged inside, too—that is, if my soul were a bar of iron, then all the rust had been banged off and the shiny metal exposed.

I didn’t bother with a shower no matter how Nesli insisted, just rinsed my hair and then rubbed in some sesame oil (a dab’ll do ya). In the morning, my hair was soft without the wet look that was in in the ’50s. I got the idea from the Odyssey: after Odysseus washes ashore and some king’s daughter lets him clean up and swab himself down with a little olive oil—one of the scenes that stuck with me from a high school reading of Homer.

The next day we left for a new venue.

PATAROS (PATARA)

I had brought with me only three books: Seven Greeks and Tatlin! by Guy Davenport, and your Combinations of the Universe.

Nesli brought Borges (yes, she brought the Book of Sand to the beach) and two volumes of poetry by Octavio Paz (all in Turkish translation). Not bad summer reading for a gal who isn’t remotely a lit major.

Near Patara, the plaj as the Turks call it (borrowing from the French), was even better than Ölü Deniz—because it was all sand; there were even dunes the size of hills. Neslihan had a smile that took up her whole face and was washed away—the smile—by every wave, so she’d laugh and smile some more. She is afraid of deep water, fears even the approaching tumescence of a wave so she rarely wades in over her head.

The road back to our new pension led through the old city, which consisted mainly of an amphitheater recently reclaimed from the dunes (alas, it has no view of the sea having been cut into a hill that rises above it), a bath complex with a dense date grove in front of it, a three-arched Roman gate built around 100 AD by some Roman governor, and the distinctive Lykian tombs ubiquitous in this part of Turkey.

Near the amphitheater, I snagged a few pieces of pottery (terra cotta), which archaeologists had clearly piled up in a rubbish heap because, I assume, the jugs were uninteresting—unpainted, in too many fragments, maybe nothing special to begin with. I couldn’t help it. You’re not supposed to remove anything from these sites, but these fragments were piled with modern refuse, and I knew they were just going to be reburied. So now these fragments of hand-worked clay more than a millennium old (Pataros has been uninhabited since the Arab invasions of the 7th century) are on a shelf in my living room along with colorful stones, a length of driftwood, sea shells, and contemporary pottery—a shelf arranged very carefully by Neslihan (“It’s my concept,” she always says.)

XANTHOS

You’ve already heard the history—somewhat more interesting than the ruins as it turns out particularly because the Brits hauled the best stuff off to London. This made Neslihan furious. “Who gives them this right?” she kept saying. But she was also furious with the Turks because in spite of lots of work to be done—digging, restoration, deciphering, etc.—excavations all over ancient Lykia were being carried on at a pace that would barely keep up with deterioration. In some cities there was NO archaeological activity.

Xanthos overlooks a valley—and a river runs through it (the valley that is). This fertile valley was what had made it so coveted.

Rising above the amphitheater built by the Romans were two Lykian tombs. This is a Lykian trademark, putting tombs on pillars. Whoever these two were, they pretty well hovered above the city—spread out in front of them—and had a nice view of the river and the valley behind them. Not to mention season tickets to every show.

In Fethiye, some of the tombs were cut into the sheer rock. More on sarcophagi anon.

The most interesting part of these ruins was the “obelisk”—actually another pillar tomb though only the pillar remains. Its 4 sides are covered by the longest Lykian inscription so far discovered—about 250 lines, including 12 lines of Greek verse. Since Lykian hasn’t been completely deciphered, my guidebook says, “understanding of the inscription is based on this verse … which tells the story of a … champion wrestler who goes on to sack many cities…”

The writing looks almost like a cheesy Hollywood attempt at alien scribbling, and a lot of the letters were borrowed from the Greek—T, E, M, P among them.

Neslihan and I were more sorry than ever that we didn’t have a camera.

THE NIGHT OF THE GHOST CRABS

Our second night in Patara, Neslihan decided she wanted to take a “short-cut” back to the pension. You know from the quotation marks this is going to be like the time Porky or Spanky or Alfalfa suggested a “short-cut” it turned out to be anything but.

Sandals in hand, spent waves washing over her feet, Neslihan headed down the beach backgrounded by a sun setting into the sea. I followed, carrying my sandals as well.

Something scurried across the sand and disappeared. An insect? I was curious but it was gone. In fact, I wasn’t even sure I’d seen it. Then there was another one. And this one did the same vanishing act. About 100 yards down the beach, I saw a third, his streak to safety lasting no longer than the immolation of a falling star. By the time I came across another, I was ready. When I cut off his path of retreat, he had to detour toward the water. It was either a tiny, nearly colorless crab or a turbo-charged glass spider. I called Neslihan over while I kept the little guy between me and the water.

“He’s so fast!”

I was still mesmerized by the speed as well—and then a wave took him.

“What is that?” she asked.

Without thinking or knowing where the answer came from I said, “A ghost crab.” I must have seen them on a nature program at some point, but I had no recollection of the documentary; it was a latent memory, and I’m still not sure whether I hit on the right nomenclature.

As we walked, more alert now and the light rapidly fading, we saw more of them—a faery quality to these striations in the dusk.

Neslihan started to count; she gave up at 50.

Then she noticed holes in the sand. Perfectly round, about the width of a pencil.

“That’s how they disappear,” I said.

Sure enough, the next time we saw one, that’s where it went, sideways into a hole, like a bullet firing back into the gun’s barrel. The pixie dust had begun to cling like wet sand, the magic to wear off a bit.

Then we noticed some holes that were a lot bigger—big enough for a golf ball.

Were those hatchlings we’d seen?

The quest to corner an adult ghost crab melded imperceptibly with the hunt for the road Neslihan insisted would take us back to the pension.

And then, at a distance, the dark pretty well settled, I saw a shape at about 15 yards that HAD to be an adult—the babies were much too small to see from that far away. But it was gone long before we caught up to it.

There was another, much closer, and even though it disappeared into the water, I had been able to see it was about half the size of my hand.

And we thought the babies were fast!

Leaving the waterline for a sort of clearing and what might lead to a road that in turn might lead back to the town and our pension, we found ourselves among dunes that would have made Lawrence of Arabia feel at home.

And then I saw it: a full-grown ghost crab a long way from its hole. It covered 10 yards in about a second; in another second, it buried itself, straight down, in one of my footprints.

But I’d fixed the spot in my sight, and when I got there, I was able to just make out bits of exposed shell. With a finger I brushed away some sand because Nesli couldn’t make him out. He was about 5 inches across and maybe a little whiter than what he was buried in. Before he was completely uncovered, his eyes popped up on stalks.

I let him be. We’d seen one up close and personal, a big one.

But we never found the road and had to walk back down the beach in serious darkness—the moon was covered by clouds, and there were only a few stars that weren’t. And no lights other than a boat well out to sea.

Neslihan was afraid—the dark scares her more than deep water—but I kept telling her there’s no one waiting around for a couple of tourists who stayed at the beach too late; it’s just not a very lucrative strategy.

She kept apologizing for the short-cut, I kept telling her not to worry about it: “What’s a vacation without a little adventure?”

After what seemed an hour, we found the paved road that cut through Old Pataros and, on the way back, we saw the silhouette of the amphitheater by star light. Embedded it in its hill, it was about 100 yards away.

“This isn’t so bad, is it?

We heard some cow bells dink and dang and dinkle here and there, which was not surprising since, during the day, we’d seen the animals themselves grazing. There had even been a bull tied to a tree in the date grove beside the Roman baths. What was surprising was that the ones we caught sight of in the dark were still munching grass.

Finally, we came on the three-arched Roman gate, which might have been even more beautiful against a backdrop of stars than the amphitheater, mainly, I think, because we were so much closer to it.

Neslihan’s fear melted. She was desperate for a photograph but I reminded her that even if we had had a camera, we didn’t have a tripod or the 1000 ASA film for a shot like that.

Before we made it to town, we saw a satellite overhead (too fast and high to be a plane, too slow to be a UFO) and, just before we got to town we saw a falling star, a pretty big one that made an orange streak over the wooded hills on the western horizon.

I tried, back at the pension, to compose a poem, but it didn’t quite come out.

PATARA

Guttering stars steadied themselves,

dusted the beach dunes with chalky light.

We were surprised to see one of them fall,

heavy with iron judging

by the orange of its funeral pyre.

The hurtling blurs near the water’s edge

were ghost crabs vanishing

like sea foam into the sand.

Hopelessly lost among the silhouetted ruins

of a Lykian city, we heard the bells of cows

grazing in the dark,

saw, arcing among the constellations,

a satellite—radio, tv, spy, who knows?

Unexpectedly, as though emerging

from underground passages,

we found our way out

through the three-arched Roman gate.

Although I write poetry from time to time, those poems come to me—kinda like beggars with their hands out. Whenever I go to them, I get a collection of images, not an aesthetic whole (see the above).

KAS(H)

After all the photos we missed in Patara and Xanthos we decided to get a disposable camera first thing in Kas (pronounced Kosh). Another $25 or so.

Neslihan went on her first scuba dive … to a depth of around 14 feet.

I did two dives: 62 feet, 70 feet. Didn’t see anything spectacular, but it had been two years since my last dive so I really needed to refresh my memory. And what snorkelers will never know is the feeling of being part of the ocean environment, of being weightless—when you’ve adjusted your buoyancy properly—of becoming, for 30-45 minutes, another form of sea life. That is what I enjoy most, adding myself to the seascape—not just “seeing” pretty fish or sunken amphorae (which I did) or catching sight of an octopus, which is all very nice, but adjusting to the rules of the underwater world. I’m always sorry when I have to come up.

As for Nesli, she is decidedly less afraid of deep water when she can breathe under it.

Now Kas is a nice little seaside town with the usual Lykian tombs in the oddest places—in a restaurant’s backyard, on the side of the road, cut into the rock cliffs rising behind the town (we got some night pictures of these).

Now Kas is a nice little seaside town with the usual Lykian tombs in the oddest places—in a restaurant’s backyard, on the side of the road, cut into the rock cliffs rising behind the town (we got some night pictures of these).

After our dive we took a ride in a greasy, turquoise-blue tub to a secluded little beach with rock tombs carved in the austere cliff face looking down on this quiet cove. We hiked up to the tombs first thing and stopped in a tiny cave on the way. The cave overlapped some with the Davenport I happened to be reading—“Robot,” a gorgeously written tale about the discovery of Lascaux. More of this anon.

One of the tombs had a half-obliterated Lykian inscription over it. I climbed the rock face to get into a niche above the tomb—a little stupid on my part, certainly some risk of falling and breaking something like an ankle, and I was a bit nervous coming down (the one rock-climbing outing I went on, we learned going up is the easy part … coming down, you gotta lead with your feet, not hands and eyes and it’s … a little scary). Neslihan made it worse by worrying out loud.

I climbed, clung, sweat, and cut my shoulder on the stone, which was quite sharp, had a pitted volcanic look to the surface although it’s not dark, not so ready to crumble, is stained various shades of ocher and orange-brown by oxides and is quite beautiful as colors go. Of course, I thought of all this after I was safely on the ground again.

The trees and plants, by the way, are picturesque in the way they match the stone—thorny, a little stunted maybe, but tough, resilient, survivors. So we decided to bring home a souvenir: the branch of life, we started calling it. It was a twisted tangle of bush, a natural broom almost, but a very wide-bristled broom, which Nesli decided was indispensable to her “concept.”

In the second tomb, I found an empty cigarette pack. “This was supposed to be someone’s final resting place,” I said to Neslihan and tossed the Marlboro box onto the hillside. That’s what they’re stealing, I romanticized, not a few grave trinkets, but someone’s eternal rest.

At the top of the hill we found another tomb, the pillar type. There’s a hole in every tomb—oddly, a panel is usually broken out although the panels don’t look real; it’s more like the surface is carved to suggest panels. The tombs remind me of eggs that have had yolk and albumin sucked out leaving the shell intact. This tomb had the grandest view of all. I joked with Neslihan that I would petition the Turkish government to be sealed up in it when my time came if she’d agree to join me on her appointed day. We took a couple of photos next to the plundered bone-box and then headed back down for a day of swimming and kayaking (free!).

Had a fish dinner (what else?) while watching the sun set in the west and there in the south more or less, lights began to twinkle on Meis, a Greek island close enough a decent swimmer could make it from Kas.

Neither Neslihan nor I wanted to leave Kas, but there were budget and time constraints. So, on our last morning, good and early, we went down the amphitheater—would’ve been a great place to smoke a cigar if only it had been evening and windless (I find the experience is disrupted when the smoke is carried off before its time). Built by the Romans, the amphitheater seated about 4,000. What a spot they picked! It faces south, the sea, the islands and, depending on the time of day, you can watch the sun rise (over the hills and the town) or set more or less into the Mediterranean. So there it was

Above the moon-bright sea,

Below the broad-faced sky

as the mediocre imitator of Homer might have said … maybe “bright-skinned sea” since the Moon was nowhere to be sea’n just then? We’d actually gone there the previous evening when there was a moon and watched some Italian children give a pretend performance while their parents sat in the upper-echelon seats. But we thought it too dark to get the proper feel—and were right.

Really, I don’t know why the Turks don’t restore and revive these places; what’s better than the human carved out of the natural? A statue, a pedestal disappearing under fallen leaves in the middle of a forest? Central Park surrounded by New York? Isn’t that the attraction of ruins? Nature reclaiming the line that’s too straight, the paint that’s too bright, the shape that’s too geometric? You can’t invent the shape of a melted candle. You can’t foresee how a building or a city will give in to the elements. It’s the beginning of Gothic, the erosion of the ideal, of the classical—which is more beautiful to us flawed humans than perfection (ultimately we love best what mirrors ourselves). What is it Blake says? “Greek is mathematical form, Gothic is living form.” But I digress.

RETURN TO KAYAKÖYÜ

After taking a bus back to Fethiye (the “branch of life” lighter than anything else we carried but so delicate it was more work in its own way), we decided to backtrack. We didn’t get to Kayaköyü until the light was pretty well spent. And it occurred to me, walking the winding paths through the town, that Kayaköyü was, very tangentially, like a more intimate Monument Valley—the weird stone shapes, the semi-silence and near-desolation, but this Monument Valley was squeezed down, labyrinthine, and sloping, tucked in wooded hills rather than spread over a desert plain. There is also, of course, the fact that these were homes, not rock formations, each one very similar to the next, but each with its own personality, facing its own direction or settled onto its own level, fixing its own gaze. Very unlike the rows of houses on modern streets facing each other in embarrassed silence.

The more Neslihan and I walked around, the more we enjoyed the place. Unlike the ancient ruins, Karmylassos had the feel of something that still had some of its original spirit about it—a shadow of the numinous? And we both thought: how could you not be happy living here? Of course, that’s romanticizing without ever having lived a day of the town’s heyday, which surely had its share of unrequited love, overly strict traditions, unfulfilled dreams, plain old boredom. And the setting, idyllic as it was, would probably be a good deal less striking if that was where you’d grown up. Nonetheless, Neslihan looked around and said, “How could they bear to leave this place?”

The truth is, they couldn’t. The Greeks who’d lived there clung fiercely to the land, their homes, their way of life, and Neslihan, I think, more than I, grokked their tragedy. Stopping in front of a stairway that wound up into the town, she was nearly in tears.

“People were going up these stairs to their homes, up and down these stairs, and then one day they were leaving … they were coming down for the last time …”

This is what she most remembers about Karmylassos, the stairway among ruins, sprouting weeds from between its stones, now used more often by goats than people.

From my journal: Finished “Robot” this morning, about 1:30 or so.

This evening, after it got dark, we sat down at an outdoor table in Poseidon Café on the edge of the ghost town and ordered a couple of wines. In spite of the name, the wall and ceiling behind the bar are decorated like a cave wall—cheesy attempt though it is with five-pointed stars, very crudely drawn reindeer, turtles, and dolphins, among other animals, in white chalk on a black background. Odd coincidence considering “Robot”—pronounced Ro-Beaux—is the name of the dog that helped three French boys discover those magnificent caves in France.

One more bit of overlap with “Robot” that I must mention … a passage that reads:

—Reality is a fabric of many transparent films. That is the only way we can perceive anything. We think it up. Reality touches our intuition to the quick. We perceive with that intuition. Perhaps we perceive the intuition only, while reality remains forever beyond our grasp.

Compare this to a passage from a story due out later this year3:

“… I wonder if truth isn’t simply a matter of the way we view things. Perhaps the world can be read in different ways. There is, of course, the truth of the senses—what we believe because of what we see with our eyes, hear with our ears, touch with our hands. There’s the truth of the intellect, which puts things in terms of causes and effects, patterns and laws. Finally, there’s the truth of the soul, which is poetic and measures according to its own harmony or discord, according to the melancholia or expansiveness it experiences.”

[…]

“And which one is truly true?”

Ibn Oraybi stroked his beard. “I imagine three veils fluttering over our eyes; only when they’re perfectly aligned, only then do we see things as they were meant to be seen.”

yeah, sure, Guy is more accurate, but then my character comes up with this notion in the 19th century, and he is rather more confident than the author who thought him up and so overstates the case somewhat. Now if some student or other looked over my work and came across the passage in “Robot” and maybe one of my book reviews praising Guy’s work to the high heavens, he would no doubt be certain this graph in “Robot“ was the inspiration for “The Three Veils“! A worthy if prosaic theory but incorrect. As it happens, the more romantic explanation is correct: the aether communicated a similar thought to Guy and me entirely separately. I also find it worth noting that my metaphor would never have taken the form of veils if I hadn’t been immersed in Turkish culture at the time I wrote it.

The Poseidon, with its embarrassingly badly rendered “cave paintings” had no walls other than the one behind the bar and, since the air was quite still, I decided to light a cigar. As though somehow the smoke could amount to an offering, and Neslihan, who reviles cigarettes and generally discourages me from my tobacco habit, took a few puffs as well.

The families deported from Karmylassos, my guidebook says, had never seen Greece.

Oddly, with darkness filling in the spaces, the town looked almost as though it were still inhabited.

Both reluctant to leave, we wished we’d brought sleeping bags. We wanted to experience at least one full night, one set of dreams, one dawn, one morning in what was left of one of Turkey’s quietest tragedies—it was a cemetery of sorts, but you’d be hard-pressed to say exactly what is buried there.

12 ISLANDS

Our last day in the south of Turkey, in Fethiye, we spent on a boat tour of 12 islands. This sounds much more exciting than it actually is. Essentially, you are on 90 feet worth of boat with 38 strangers—and you go to an island, the boat anchors, everybody jumps in the water. That’s it. Swimming in about 12 different locations and a nice fish lunch. Luckily, I’d invested in a diving mask and a snorkel the day before. Neslihan and I splashed around in the shallows picking up star fish, avoiding sea urchins (the Turks call them “sea chestnuts”), watching schools of silver-bellied fish change directions in a synchronized flash, spying on transparent shrimp as delicate as spun glass, on hermit crabs, on some sort of sea slug.

On one of these dives, I salvaged a scallop shell, grayed, crusted-over with sea growth, broken. I put it on a table on the boat and Nesli decided it must be, along with the broken pottery and the “branch of life,” be part of her “concept.” The captain, however, picked it up, looked at it, and without a word, flung it overboard. Then he said, more or less, “Here, I’ve got something better for you.” He put down two immaculately white scallop shells. Neslihan didn’t appreciate the gesture. I didn’t either, but I kept my mouth shut because I knew his intentions had been the best. She wanted the other shell with all its imperfections and told him so.

I thought there was something very Turkish—Mediterranean in fact—in the confidence his gesture showed. It reminded me a Greek bus driver in Rhodes who had taken a shine to me, showed it by hurling a couple of pieces of candy at me like fastballs, and had laughed when they’d bounced off my chest. It’s just not done where I come from.

ISTANBUL

We arrived back in Istanbul tanned and already missing the south. For a couple of days, we were mildly depressed by the crowds, the rush, the cramped sky, by being separated from the sea (the Bosphorus fell short).

Incorporating everything into her “concept” (the branch of life survived the plane ride, a ferry ride, and two taxis home), Nesli wanted to know when we were going back.

Three weeks later, I’m still gazing at the south and daydreaming of getting John Ash to get Orhan Pamuk to go in on a writer’s retreat with us on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. This, I suppose, is what comes of reading Davenport with his philosophers, philosophy students, artists, and theology students with the bodies and habits of decathletes—a writer’s retreat initially but soon, a gymnasium!

Well, don’t expect another letter one like this anytime soon—this is the longest I have ever written to anyone. I don’t know why, but I felt driven—yes, this epistle showed up with fraying sleeves and hand out. Aside from whatever you get out of it, aside from recording this trip far more faithfully than my sporadic journal, helping me relive the experience, it encouraged me to think over a nonfiction piece on Kayaköyü. That’s what writer’s are really hear [sic] for isn’t it? To give voice to something or other that can’t speak for itself? Or has been forgotten? Or got nobody to listen? A thousand thousand things at least are lying in silence, dry as bones, just waiting for somebody to sprinkle a little water on them. And for something, if luck holds, to sprout. At least that’s how I see it.

Hope all is well in Wichita and I hope I haven’t given you too much homework.

Vince

Return to table of contents.